In the last several weeks, I have been building a toy browser based on an online book, Web Browser Engineering. As someone who spent a fair share of his career on web frontend, it was eye-opening and satisfying. It felt like I had been living on one side of a wall for years and finally visited the other side of the wall. I imagine other web frontend folks would like it as well.

The book

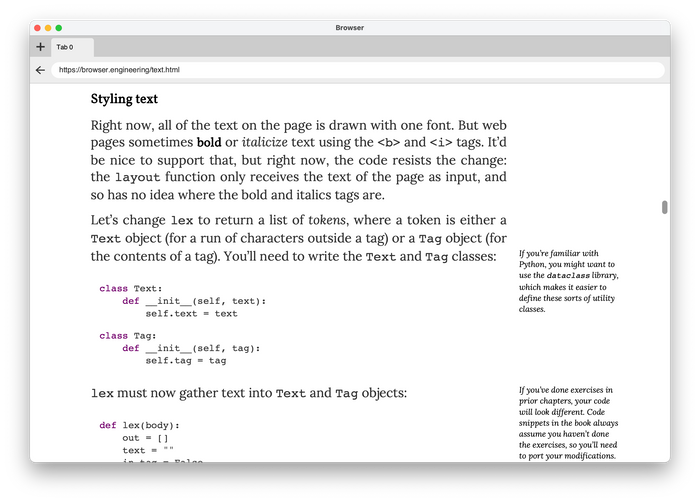

Web Browser Engineering is an online book by Pavel Panchekha and Chris Harrelson. It explains how browsers work and lets you implement a toy browser almost from scratch. HTTP, CSS parser, HTML parser, rendering pipeline (style, layout, paint), the interaction between browser window and tabs, JavaScript, animation, and the list goes on. It uses only a handful of libraries such as TCP, Tkinter (replaced by Skia and SDL in later chapters), and dukpy.

I discovered it on Twitter. Once I started reading the book, I was hooked. It presents succinct code to implement browser features incrementally. You are always with working code.

Each topic lays a good foundation that you can build upon and links to relevant resources. Exercises let you implement features on your own.

Even before the book, I had read a good amount of articles about how browsers work from outside. The book explained concepts in a way that readers could implement them. I learned a lot.

Beyond the book

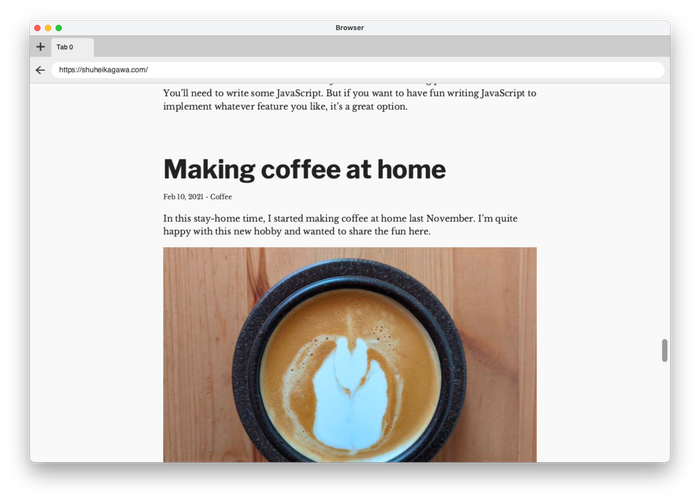

I wanted to render real-world websites. Well, real-world websites on the simpler side. Not JavaScript-driven applications. HTML, CSS, and a bit of JavaScript. This website and the book's website were my main targets. Wikipedia was a stretch goal.

The goal has been partially achieved.

Even for rendering simple websites, I had to implement or revamp numerous browser features beyond the book.

HTML

I revamped the recursive descent HTML parser from the book to support quoted attributes, raw text elements, etc. Among HTML, CSS, and JavaScript (ECMAScript), the HTML spec was the easiest to read and implement (partially).

Fun facts:

- Browsers are supposed to sniff the character encoding of a web page.

- HTML spec has quite detailed rules for tag omission.

- HTML spec explains how to handle invalid markups like

<b><i></b></i>. HTML parser never fails!

CSS and rendering

I was drawn to implementing CSS features. CSS is more forgiving than JavaScript—at least for a toy browser. Even if my toy browser missed most of the CSS features, it still rendered something on the screen. On the other hand, JavaScript halts execution on a single missing syntax or feature. I would need to implement a bunch of browser APIs until the toy browser could run real-world scripts. So, I focused on CSS and rendering for the toy browser.

While I was working on the project, my best friends were MDN and CSS specs (CSS 2 and more). Yes, there are quite readable.

One surprise for me was that CSS syntax doesn’t say much about property values. Each property has own syntax. For example, font-family and animation have different precedence rules for commas and spaces.

font-family puts commas higher precedence than spaces:

/* (1.6em) (bold) (Helvetica, Arial, sans-serif) */

font-family: 1.6em bold Helvetica, Arial, sans-serif;

animation does the other way around:

/* (slidein 3s), (move 10s) */

animation: slidein 3s, move 10s;

The book skipped whitespace handling but it was necessary for nice-looking code blocks (white-space: pre). The CSS spec has elaborate rules for ignoring and collapsing whitespace. I made up a greedy algorithm instead of implementing the full spec. It's not 100% accurate, but it looks alright.

Web fonts were essential to make my toy browser look nice. I revamped the CSS parser to support the @font-face rule and implemented rudimentary font synthesis and font matching. Skia took care of the actual rendering.

I also learned a few things about the inline layout (or normal flow). The box model is considered to be a basic for frontend developers. But did you know how the inline layout works? What's the difference between line-height: 1 and line-height: 1em? Why doesn't vertical-align help vertical centering? Deep dive CSS: font metrics, line-height and vertical-align by Vincent De Oliveira is an amazing article that explains those things.

Fun facts:

- Margin collapsing and float are hilariously complex. I implemented only a tip of them.

- CSS Fonts Module has line charts to explain the font matching algorithm. Browsers try their best to pick fonts for you without you even noticing it.

- The list counter spec is quite advanced. You can create counters, increment them and use them as part of

contentin CSS.

Other stuff

I also implemented other stuff.

- Retina display to make the toy browser look good on my laptop

- Window resizing: SDL doesn’t seem to provide a good API for resizing

- URL parsing: Parsing URLs into objects made it easier to implement many other parts of the project. I should have done it earlier.

- Content Security Policy: The CSP implementation from the book blocks legitimate requests. I implemented the bare minimum to allow legitimate resource loading.

Python

The book uses Python for good reasons. I followed the path and used Python because I wanted to focus on the subject instead of spending time on how to do X in Y language. I had already made enough (fun) mistakes of this kind in my life.

Also, it was a good opportunity for me to learn Python. Python is used in a lot of places now, but I had survived without learning it before the project. After writing thousands of lines, I like its concise syntax.

I used pyright for static type-checking along with coc-pyright on Vim. Its type inference worked quite well for me. It uses a gradual typing approach similar to TypeScript although Python’s type annotation is part of the language specification. Python’s typing features don’t look as powerful as TypeScript, but they met more than 90% of my needs. Also, auto-completion was helpful for a Python beginner.

My toy browser uses only a handful of third-party libraries. They either had type annotations or had only small little surface in my toy browser. The only exception was skia-python. I used it a lot. It didn’t have official type stubs, so I generated them with mypy's stubgen. The generated stubs were not perfect but good enough as a foundation to build upon for my limited use case.

I used black for code formatting and pytest for unit testing. I don't have much to say about them because they just worked™.

Conclusion

It’s been a fun side project with lots of learning. I imagine other web frontend folks would like it as well. I recommend you check out the book and build your own toy browser!